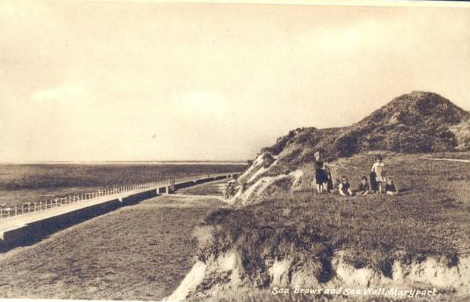

Maryport promenade, along the sea wall, is one of the town’s hidden gems, providing a superb walking environment with fabulous views across the Solway, access to a stunning beach and a wonderful variety of flora and fauna to observe and admire at all times of the year. But it wasn’t built as a tourist attraction; it was built at a time of extreme poverty and deprivation in the town of Maryport. It was built as an “unemployment relief” measure.

Up to the onset of the First World War, Maryport was a prosperous little town with a range of industries: Shipbuilding; Coal Mining; Iron Smelting; a vibrant Shipping sector; Fisheries; & as head office of the Maryport and Carlisle Railway, it housed the company’s loco shed and maintenance works. Additionally, there was all the support and cultural activities that kept the town and its industrial base together.

The last shipyard, (Ritson’s), closed in 1913, succumbing to the lack of facilities to manufacture and install the engines required by ships, the lack of fitting-out facilities and the restrictions imposed by the small River Ellen. A skilled workforce was forced to seek new work.

After World War 1, the colliery at Ellenborough closed, and 4 men from Ellenborough were killed in an explosion at the St Helen’s Colliery at Siddick. The Maryport Hematite Ironworks had closed in the 1890’s, and its neighbour, the Solway Ironworks, staggered on, through changing ownership, strikes and massive local competition, to finally close in 1927. A town that had once had twelve blast furnaces, and which, over 150 years earlier, had been the home of one of the world’s first blast furnaces to use coke rather than charcoal as the source of heat, left the Iron and Steel industry.

During World War 1, the 120 railway companies across Britain were controlled by the Government. Following the war, many of those companies had found themselves in difficulty and in 1921, Parliament passed an Act to group them into 4 large companies, hoping to reduce competition and generate economies of scale across the network. The provisions of the Act took effect at the start of 1923 & the effect on Maryport was devastating.

Maryport was the head office of the Maryport and Carlisle Railway and the location of the company’s loco and rolling stock maintenance workshops. The company, which during its more than 80 years of trading had never failed to pay a dividend, was incorporated into the new London, Midland and Scottish Railway Company, which promptly announced the closure of the railway workshops in Maryport. The town’s imposing railway station, which housed the head office of the Maryport and Carlisle Railway, its offices, and administration, the boardroom and directors dining room, would no longer be needed.

In 1900, Maryport Docks handled imports of 539,303 tons and exported 499,451 tons, a total of 1,038,754 tons. Additionally, it handled 520,214 tons of cargo, (imports and exports), from the Workington Steel industry. By 1920, traffic though Maryport docks had fallen to 334,813 tons, a fall of 68% and only a further 83,709 tons from Workington, an 84% reduction.

In 1922, the Government agreed to guarantee a £500,000 investment in a new dock at Workington, the Prince of Wales dock as it would become, an investment that threatened the viability of Maryport docks; the Senhouse dock, built in 1884, had been built with a dock gate that was too small for the more modern ships of that time. It was clear then that once the improvements at Workington docks had been completed, (in 1927), Workington docks traffic would no longer be routed through Maryport. Indeed, by 1929, the total imports and exports through Maryport docks were only 143,812 tons, with no additional trade from Workington.

Examples of other issues experienced in the area during the period between the World Wars included Agriculture when, in 1924, foot and mouth disease broke out at Hill Farm, Crosby and there was even an outbreak of Small Pox in Maryport.

Attempts were made to alleviate the desperate situation many were experiencing, for example, in October 1924 the County Highways Committee agreed to a project for the widening of the road from Maryport to Crosby, to be carried out as an unemployment relief scheme.

In 1928, the Ministry of Health Inspector unexpectedly determined that the distribution of relief funds to the unemployed of Workington and Maryport was too generous, & the National Government of 1931 cut benefits of insured workers by ten per cent.

In order to qualify for ‘dole’, a worker had to pass a means test, administered by Public Assistance Committees, (PAC), that put a worker’s finances through a rigorous investigation. Officials went into every detail of a family’s income and savings, & the intrusiveness of the means tests and the insensitive manner of officials who carried them out frustrated and offended workers.

On 9 August 1932, the Penrith Observer reported on a meeting of the Cumberland Public Assistance Committee to consider how the assistance was being administered, especially by the Maryport and Workington Relief Committees. The Government was concerned over what it described as the “over lavish relief granted in these areas.” “The main points of difficulty were as follows: where an application for transitional benefit is made by an unemployed member of a household NOT to reckon as earnings coming into the household 10 shillings, (50p), of any income earned by the employed members, this has resulted in benefit going into households where the aggregate income of its members is as much as £6 per week. Benefit can only be granted where need is proved …”

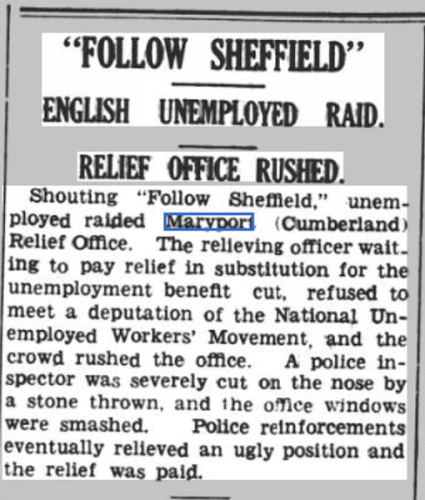

The disquiet with the system led to a riot in Maryport later in August 1932 when a mob attacked the Cumberland Public Assistance Committee’s office, smashing the door down and smashing the office furniture. Terence Murphy of Dearham was sentenced to two months imprisonment for his part in the ‘outrage’.

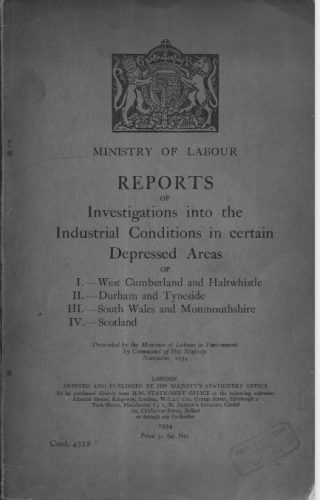

In 1934, the Appleby branch of the British Legion made grants from their Poppy Day Relief fund of £30 to Maryport and £20 to Aspatria as support for distressed areas. In the same year a Report was commissioned by the Ministry of Labour into “The Industrial Conditions in certain Depressed Areas …”

The report in full is available at Carlisle Library. Extracted parts that refer to Maryport show that the town was found to have the highest rate of unemployment in the district – a staggering 61.2%!

Page 10

“The first issue which arose … was to consider whether any, and if so which towns and villages … could be described as “derelict”. In brief, this was measured by the percentage of men unemployed and recorded at the branch Employment Office.

| Maryport | 61.2% | 1,684 men unemployed | |

| Cleator Moor | 57.3% | 2,210 men unemployed | |

| Cockermouth | 45.3% | 588 men unemployed | |

| Aspatria | 37.0% | 505 men unemployed | |

| Whitehaven | 32.3% | 1,810 men unemployed | |

| Workington | 31.7% | 1,784 men unemployed | |

| Harrington | 28.2% | 451 men unemployed |

Page 11

Maryport was described in the report as “partially derelict”, (incidentally Broughton Moor was described as “derelict”), & the condition of Maryport was “… said to be “desperate” and the town to be “… for the most part living on public funds.”

Page 13

“Maryport covers the sorely hit villages of Flimby, Broughton Moor and Dearham, whose state is in some respects more depressing than that of Maryport itself.”

“… Some of the worst hit towns are neither ill kept nor dilapidated. Maryport for example still presents a good appearance and from the land is neither dismal nor depressing, though from the sea the almost deserted docks dominate the town and lend colour to the description of the town as derelict.

The town contains a number of good-class houses, many of which are … inhabited by retired persons – seagoing engineers, ships’ officers etc. There are no obvious signs of severe distress either in the appearance of Maryport or its inhabitants.”

Later in 1934, the government, (a ‘National Government’ established to deal with the aftermath of the Great Depression), passed the ‘Special Areas, (Development & Improvement), Act, with the aim of providing aid to the areas of the country with the highest levels of employment. The Act identified South Wales, Tyneside, West Cumberland and Scotland as areas with special employment requirements, and invested in projects like the new steelworks in Ebbw Vale. It was reported in the Lancashire Evening Post of Saturday 13 July 1935 that the Council, (Maryport Urban District Council), had received a letter from the Commissioner for Special Areas stating that he was prepared to ‘consider making grants towards the provision by local authorities of hospitals, maternity & child welfare centres, & of open-air swimming baths’.

The success of the Act was limited because the level of investment was not high enough and it was not until the late 1930s that the shadow of unemployment lifted from Britain, thanks in part to government investment in re-armament. Despite the failings of government action, few people actually starved to death as a result of unemployment; the dole was intended to keep the unemployed alive and it had done exactly that.

It was a time when many moved away from the area looking for work. For example, there was a General Drapers at 118 to 120 Crosby Street, owned by A A Gardiner for some forty years until 1920, when it was taken over by Coulthards, until the business moved to 42 Senhouse Street in 1935. Shortly after this, the owners moved away to Birmingham seeking work. For those that remained, there was a good deal of disquiet due to the level of unemployment. One result of this was manifested in February 1935, when the unemployed of Maryport ‘expressed their frustration’ by rushing & causing damage to the ‘Relief’ Office.

Maryport Harbour was frequently impacted by extreme weather which could cause damage & protection works were needed on occasion. For example, the Carlisle Journal of Saturday 5 September 1840 reported that, ‘The Trustees of Maryport Harbour have commenced the erection of a breakwater, at the north side of the harbour, by which it is expected that the heavy seas frequently experienced within the quays during the westerly gales will be eventually checked’.

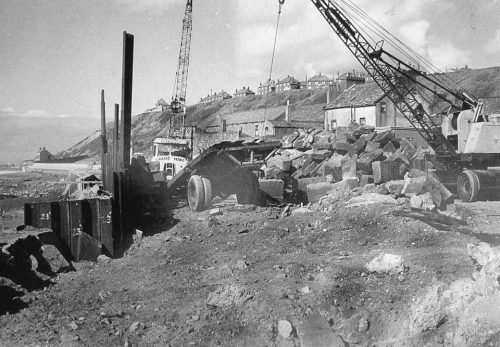

On 9 January 1936, a tremendous storm combined with a high tide caused a great deal of damage to the harbour and dock gates at Maryport. It was reported in ‘The Scotsman’ & the ‘Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail’ on 14 January that the port was in danger of permanent closure as a consequence of the damage, which had ‘invaded the streets of the town’ & swept away fifty yards of the south pier & badly damaged the north pier, quays & both sea walls. Whilst temporary navigation lights, powered from a gas cylinder, were erected to enable the port to re-open on 13 January, the Harbour Commission, which had just received a grant for essential dredging work from the Special Areas Fund, had run out of resources & had to apply for funding to the Commissioner for Special Areas. It was stated in the aforementioned publications that, ‘the view is officially held that unless another grant extending to five figures & possibly six is forthcoming to repair the damage, the port is virtually finished’.

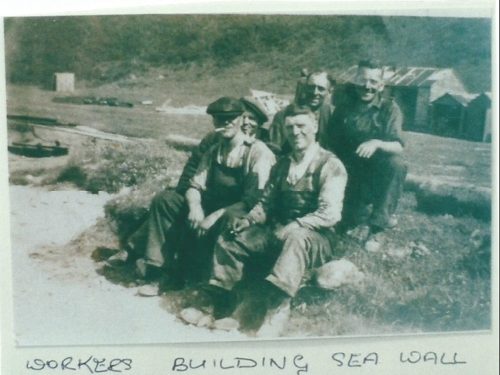

Maryport Promenade was built by the unemployed men of the town

In April 1936, the Maryport Harbour Commissioners had been given an indication that, following a visit to the town by the Commissioner for Special Areas, Mr Malcolm Stewart, he strongly supported their application for assistance. The Liverpool Journal of Commerce of Monday 5 September 1938, under the heading, ‘Terms of Grant Accepted’, reported that, ‘A meeting at Maryport of the Maryport Harbour Mortgage Bondholders voted, with one dissentient, in favour of accepting the terms of the Commissioner for Special Areas respecting the grant to recondition Maryport Harbour & Docks. The terms for a loan of £50,000 & grant of £25,000 are that maintenance, sinking fund loan interest & bond interest shall rank in that order, & that the harbour capital be written down to £100,000.’ It was later reported in the Lancashire Evening Post of Friday 14 April 1939 that plans for the reconditioning of the harbour & docks, at a cost of £98,000, were discussed between local officials & Sir George Gillett, Commissioner for the Special Areas of England & Wales, on 13 April.

The image below shows the damage to the sea wall.

It had been reported in the Liverpool Evening Post on 16 November 1935 that the owner of the Sea Brows & foreshore, Lieutenant-Colonel Polkington-Senhouse, was prepared to sell that land to the council, (Maryport Urban District Council), for £1,500, provided that it erected a sea wall stretching from the gas works at the Brows’ southern end to Bank End Farm in the north, to protect it from sea erosion. In the same year, Sir Cyril R S Kirkpatrick, (Consulting Engineer), advised Maryport Urban District Council that he was prepared to develop a report on the proposed sea wall with a 20 foot, (six metre), carriageway fronting the Sea Brows. The report was subsequently agreed, with provisional approval for Government Special Areas Grant aid for a scheme to construct a sea wall at an estimated cost of £44,000 given in May 1936, (following the devastating damage to Maryport Harbour caused by the storm in January 1936).

At its meeting held on 4 June 1937, Maryport Urban District Council considered tenders from 13 companies, & the scheme attracted submissions ranging from around £50,000 to £80,000, well above the estimated cost, reflecting the rising cost of materials at that time. The Lancashire Evening Post of Saturday 19 June 1937 reported that, subject to the approval of the Ministry of Health, Maryport Urban District Council had decided to accept a tender of £50,772 for the erection of the new sea wall & carriageway fronting the Sea Brows. The Council also notified the Harbour Commissioners, it was reported, that it was prepared to take over the Maryport Harbour bridge, linking Shipping Brow with the South Quay & Irish Street, if the bridge was reconstructed as part of a harbour improvement scheme.

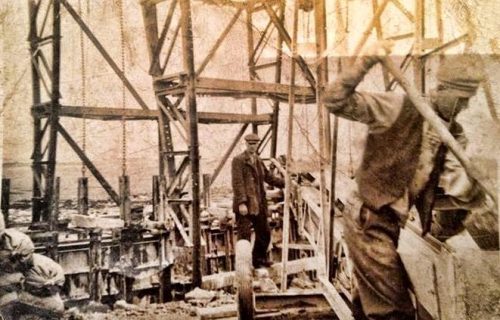

Government Special Areas Grant of 100% funded the sea wall scheme, it was reported in the Lancashire Evening Post on Saturday 3 July 1937, & work, estimated to take some fifteen months, carried out by contractors Van Hattum’s Harbour Works Ltd of London, was due to commence, the newspaper reported, ‘as soon after Thursday as the contractors……can get their plant on the site’. The contracting company was the British arm of Van Hattum, a Dutch civil contractor which carried out harbour works, sea defence & dredging in Holland, (& still exists today as ‘Van Hattum en Blankevoort’). As an unemployment relief scheme, the construction work supported the employment of local unemployed men, with preference given to married men of 35 years of age & upwards with families. Each man was given work for just six weeks, before returning to ‘the dole’. The Lancashire Evening Post of 3 July 1937 report stated that, ‘employment will be given to about one hundred men for that period’.

Hard Labour

It is believed that the sea wall is ‘keyed’ into the bedrock, thus preventing the wall from moving forward, unlike the stepped sandstone wall at the end of the North Pier, which is understood to be a ‘gravity’ structure, relying on the weight of material to keep it in place. The sea wall was built in sections of concrete in a design to reflect the power of the waves up & then back towards the sea, reacting with the incoming waves & reducing their power.

The Yorkshire Post & Leeds Intelligencer of Tuesday 21 June 1938 reported that, ‘At a meeting of Maryport, (Urban District), Council yesterday, it was disclosed that the Commissioner for Special Areas had approved an extra grant of £5,000 excess expenditure over the estimate for completing the sea wall & promenade now being built’. Additionally, it was reported that, ‘The National Fitness Council have also granted £5,000 for an open-air swimming pool adjoining the new promenade’.

The project was completed by January 1939 & the Commissioner for the Special Areas of England & Wales, Sir George Gillett, visited Maryport in April 1939 to inspect the finished work. It was reported in the Lancashire Evening Post of 14 April 1939 that local representatives expressed their appreciation of the interest Sir George had taken in the welfare of Maryport & the assistance he had provided in procuring grants.

It was subsequently reported in the Lancashire Evening Post of Friday 5 May 1939 that Maryport, (Urban District), Council had been informed by the National Fitness Council that it was prepared to extend its original offer & make a grant of £8,000 towards the open-air swimming pool. ‘The pool will be attached to the new sea wall & promenade, recently completed at a cost of approximately £50,000, by means of a grant from the Commissioner for Special Areas. This grant of £8,000 will leave the Council with £1,750 to find towards the estimated cost of the bathing pool, which it would ‘probably raise……by means of a loan’. Despite the offered funding, the pool was never built & it may be that the ongoing uncertainty in Europe at that time, immediately prior to World War 2, had an impact on plans.

Two pictures below, taken from postcards, show the completed promenade post-1939, looking towards the location of the shelter added at a later date. The other pictures below show parts of the completed promenade in later years.

Footnote

In researching the history of the sea wall & promenade, the contributors found other information of interest but not directly related.

The Special Areas Fund benefited the area in other ways. It was reported in 1937 that, ‘Foundation stones were laid….of the new maternity wing of Maryport Hospital, which is to cost £10,000, of which £6,000 has been granted by the Special Areas Fund & £1,000 by the county council.’ The new maternity wing opened in June 1939.

Of particular interest was the assistance given by the people of Portsmouth to the Maryport area. Under the heading ‘Distressed Town’, ‘How Portsmouth could help’, ‘Adopt Maryport’, the Portsmouth Evening News of 27 November 1937 carried an article which referred to Maryport as a once busy coal mining & ship building town but latterly a ‘special area, where 1,523 people in an insured population of 3,360 are unemployed’. The Portsmouth branch of Toc H suggested that Portsmouth could take its place in a scheme whereby a fortunate town ‘in regard to its comparative industrial prosperity or stability helps another upon which industrial depression has laid a crushing hand’. It reported that neighbours Bournemouth were helping the ‘stricken village of Southchurch, County Durham’, & suggested that Portsmouth adopt a similar scheme.

The report noted that prior to World War 1, ‘Maryport was a busy place with coal mining, iron works, ship-building, tanneries, engineering shops & other trades mostly connected with the Maryport & Carlisle Railway, whose headquarters were there’. The report stated that Maryport was ‘the home port of a local fleet of seven or eight steamers of from 3,000 to 4,000 tons each’, which ‘carried coal & steel rails to various ports & brought in iron ore, chiefly from Spain’, adding that, ‘the fleet abandoned its operations nearly thirty years ago’. ‘A prosperous ship-building & timber yard was closed down together with seven collieries. All that is left is one colliery & a newly opened small drift. Iron works have been transferred to Workington & the result was that the harbour could not pay for its upkeep’. The report added that, ‘except for the building of a sea wall at a cost of £50,000, there is little labour in prospect. Such are the grim facts about Maryport & it is not difficult to realise why it was recently spoken of as a “ghost town”.’

Portsmouth Toc H advised that through its Workington branch, it had secured the assistance of the Maryport Branch of the Personal Service League, of which the secretary had volunteered to distribute, ‘to the most deserving cases any clothing, footwear, bedding etc that can be sent’. Through this connection, it was hoped to, ‘build up gradually a personal connection with individuals & families in Maryport’.

The Portsmouth Evening News of 4 March 1939 reported on the ‘Maryport Scheme’. It stated that ‘Some time ago, the Maryport Scheme was started. Its object was to utilise the philanthropy of the citizens of Portsmouth towards helping the unfortunate inhabitants of this town, which is in a distressed area. Mr L B Benny, Chairman of the Organising Committee, says that although no public appeal has been made, the scheme is meeting with every success.’

Another interesting &, perhaps in part, amusing report appeared in the Leicester Daily Mercury of Monday 14 January 1946, under the heading, ‘Mine Immobilised’. The report said that ‘The fuse of a 1,200 pound British mine, which rocked at the end of a hawser ten yards from the sea wall at Maryport, Cumberland, all day yesterday, was removed by a Liverpool mine disposal squad late last night. Three men volunteered to keep working at the gas works nearby to ensure that Sunday dinners should not go uncooked. Forty families were evacuated from their homes & NFS tenders stood by in case of fires should the mine have exploded.’

Contributors

Maryport Town Council is indebted to the following local historians for their extensive research in providing the information on which this narrative has been based:

David Malcolm, for the basis of this narrative

Raymond Greenhow, for his research into newspaper articles

Dolly Daniel, for her research into newspaper articles