Historic England

Designation of Maryport Coke Ovens as a Historic Monument

Official list entry

| Heritage Category: | Scheduled Monument |

| List Entry Number: | 1019211 |

| Date first listed: | 18-Jul-2000 |

Location

The building or site itself may lie within the boundary of more than one authority.

| County: | Cumbria |

| District: | Cumberland |

| CouncilParish: | Maryport |

| National Grid Reference: | NY 03561 36293 |

Reasons for Designation

Coal has been mined in England since Roman times, and between 8,000 and 10,000 coal industry sites of all dates up to the collieries of post-war nationalisation are estimated to survive in England. Three hundred and four coal industry sites, representing approximately 3% of the estimated national archaeological resource for the industry, have been identified as being of national importance.

This selection, compiled and assessed through a comprehensive survey of the coal industry, is designed to represent the industry’s chronological depth, technological breadth and regional diversity. Coking is the process by which coal is heated or part burnt to remove volatile impurities and leave lumps of carbon known as coke. Originally this was conducted in open heaps, sometimes arranged on stone bases, but from the mid- 18th century purpose-built ovens were employed.

By the mid-19th century two main forms of coking oven had developed, the beehive and long oven, which are thought to have been operationally similar, differing only in shape. Coke ovens were typically built as long banks with many tens of ovens arranged in single or back-to-back rows, although stand-alone ovens and short banks are also known. They typically survive as stone or brick structures, but earth- covered examples also exist.

Later examples may also include remains of associated chimneys, condensers and tanks used to collect by-products. Coke ovens are most frequently found directly associated with coal mining sites, although they also occur at ironworks or next to transport features such as canal basins. Coal occurs in significant deposits throughout large parts of England and this has given rise to a variety of coalfields extending from the north of England to the Kent coast. Each region has its own history of exploitation, and characteristic sites range from the small, compact collieries of north Somerset to the large, intensive units of the north east.

All surviving pre- 1815 ovens are considered to be of national importance and merit protection, as do all surviving examples of later non-beehive ovens. The survival of beehive ovens is more common nationally and a selection of the better-preserved examples demonstrating the range of organisational layouts and regional spread is considered to merit protection.

The coke ovens at the south end of Furnace Road are considered to be the oldest in the country and possibly the world. Their form is unique, being quite different from the normal beehive type, and documentary evidence dated to 1783 refers to them as being a new design.

Details

The monument includes the buried remains of a bank of six mid-18th century coke ovens located at the southern end of Furnace Road in Maryport. These ovens were used to produce coke for the adjacent Netherhall blast furnace. A combination of limited excavation and documentary sources has shown that they were built sometime after the blowing-in of the furnace in 1754 but before the final sale of the blast furnace in 1783.

The ovens are constructed of dressed sandstone and lined with brick and are of an unusual non-beehive form. They are best described as rectangular barrel-vaulted form with an unloading door at the front base and a flue and/or loading chute at the rear top. The ovens differ from each other in minor detail and some show evidence of alteration. On present knowledge these are considered to be the oldest coke ovens in Britain, and therefore probably in the world.

The buried remains of a bench for the emptying of the ovens and loading of barrows is expected by the site excavator to survive on the hillslope immediately beneath the row of ovens, and this small area is also included within the scheduling. All modern stone retaining walls and a flight of wooden steps are excluded from the scheduling, although the ground beneath these features is included.

The site of the monument is shown on the attached map extract.

Legacy

The contents of this record have been generated from a legacy data system.

| Legacy System number: | 32857 |

| Legacy System: | RSM |

Sources

Books and journals

Cranstone, D, ‘Journal of Historic Mining Society’ in Early Coke Ovens: A Note, Vol. 23/2, (1989), 120-1

Other

Gale, D, The Old Maryport Blast Furnace, Unpublished excavation report

Letter to Dr M. Nieke, Gale, D, (1988)

Legal

This monument is scheduled under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979 as amended as it appears to the Secretary of State to be of national importance. This entry is a copy, the original is held by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport.

Coke in West Cumberland

Extracts from an article by John Martin first published in the

Cumbria Industrial History Society’s Bulletin

Early Days

Coke is what remains when coal is heated to a fairly high temperature out of contact with air. Not all coal will form an adherent mass of coke, but that which is mined in West Cumberland can rightly be termed “coking coal”.

Prior to 1700, the production of iron from its own ores was achieved by mixing the ore with charcoal in a shaft furnace, and, after igniting, blowing air into the lower part of the furnace. The charcoal burned to provide the necessary heat and it also combined with the oxygen in the ore, leaving the metallic iron in a molten state to be collected in the base of the furnace and eventually run out into moulds to solidify.

Charcoal became scarce as the forests were denuded, and the iron makers eagerly sought a substitute. Raw coal proved quite unsuitable, but by submitting it to the same treatment which was applied to wood for the production of charcoal, they produced a coke which after many trials proved to be a satisfactory substitute.

Charcoal was made by building logs into a dome shape structure, covering it with earth and firing it, openings at the top and base being provided to create a through draught which could be regulated to avoid complete combustion.

The earliest known iron furnace in West Cumberland was erected at Little Clifton in 1723 using coal from the Frizington area. The owners were already mining coal near Clifton, and this they converted into coke on land adjacent to the furnace. They followed the charcoal burner’s practice by covering a heap of coal with earth and roasting it by controlled combustion.

Beehive Ovens

In 1752 another furnace was built at Maryport and here provision was made for making coke in ovens. These were brick chambers which took the place of the earth covering in the ‘heap’ method. Otherwise, the procedure was the same, some of the coal being allowed to burn to provide heat for charring the rest.

A further iron making enterprise was established at Barepot near Workington in 1763 and, here again, ovens of the type used at Maryport were erected.

These three iron making activities had all been abandoned before the days when the demand for iron and improved methods of producing it brought about the beginnings of the industry as we know it today.

The deposits of high-grade iron ore in the Cleator and Egremont area had been worked for some time and shipped to other areas, notably North and South Wales and Scotland. In 1840 blast furnaces were built at Cleator Moor and in 1856/7 at Harrington and Workington. Coal was already being produced at various mines throughout the West Coast area and at several of these coke ovens of the ‘beehive’ type were erected to provide the ironworks with their requirements. As more and more ironworks were erected at Maryport, Workington, Distington, Parton and Whitehaven, more and more beehive ovens were built until every major colliery in the area had an outlet for some of its coal in this direction.

Even so coke production did not match local demand and considerable tonnages were brought in from Durham. The Durham coke proved superior to much of the local product particularly in its lower phosphorus content, a factor of considerable importance to the local hematite iron industry.

The beehive ovens were essentially coke producers. No attempt was made to recover any of the gas, tar or other by-products which were driven off from the coal when it was heated. The coal charge did not fill the oven. Space was left above the charge in which the gas liberated from the coal was burned.

By-product Ovens

An advance on the beehive ovens was made when a box like oven was designed in which the gas was led through openings in the upper part of the walls into flues where it could be burned out of contact with coal and impart its heat to the charge through the oven wall.

A battery of 24 ovens of this type was built at the St. Helen’s colliery at Siddick in 1894. Each coking chamber was 30 feet long, 6 feet 6 inches high, and 24 inches wide, and produced 4 tons of coke every 48 hours. Such ovens could not be raked out by hand as was the case with the beehive ovens, and a steam driven mechanical pusher was used which could be placed in front of each oven, and when the doors were winched up the coke was pushed out on to a flat bench where it was quenched with water before loading onto wagons.

As yet there was no recovery of any of the by-products of distillation, but in 1908 the Risehow Colliery Co. at Flimby installed a battery of 40 ovens with full by-product recovery plant. A feature of these ovens, designed by Heinrich Koppers of Essen in Germany, was the use of regenerator chambers below the ovens. Gas was taken away from the oven, cooled to condense the tar, passed through sulphuric acid to fix the ammonia and then burned in a series of flues built into the walls between the several ovens. The hot water gases were then passed through a chamber containing a chequer work of bricks before being led to the chimney. The heat absorbed by the bricks was later used to heat the air necessary for the combustion of the gas in the flues, the net result being that only some 60% of the coke oven gas was necessary for maintaining the coking process.

The Risehow battery was among the earliest by-product ovens in the country and was the first to use the ‘semi-direct’ process for the recovery of ammonia.

A similar plant was installed at the St. Helen’s colliery a year later, followed between 1911 and 1913 with installations at Lowca, Whitehaven, Moresby, Allerdale and Oughterside, until there were 409 such ovens in West Cumberland producing 12,000 tons of coke and using 18,000 tons of local coal per week. Meanwhile, as a result of a decline in the demand for hematite iron, the amalgamation of local iron making companies and improved efficiencies in the use of coke in blast furnaces, the consumption of coke in the area had substantially decreased. These factors eventually resulted in iron production being concentrated at the works of Workington Iron and Steel Company, with three blast furnaces of high operating capacity. In 1936 a battery of 53 Becker ovens was commissioned adjacent to the blast furnaces producing sufficient coke to meet their requirements and, one by one, the older batteries of ovens in the area were closed down.

Making Coke

The coke produced in the so-called ‘patent’ by-product ovens was quite different in character from that from the beehive ovens, and it was received with a certain amount of prejudice by the furnacemen. It was smaller, no piece being larger than half the width of the 20″ wide ovens, whereas the beehive coke could be up to 20-24″ long. Its appearance was also different, lacking the graphitic lustre of that to which the furnace operators were accustomed. There was an uninformed suspicion that the recovery of by-products had “taken something out of the coke”.

It took some time for this prejudice to die down, but in the course of time furnacemen learned to use the new material to advantage, until eventually they were producing good quality iron with a consumption of only 11 cwts. of coke per ton compared with a figure of 20-22 cwts. in the ‘beehive days’. This very marked economy was due to several factors, not all related to coke quality although this was materially improved as a better understanding of furnace requirements was reached. Larger furnaces, grading the size of ore and coke, the sintering of fine ore and the blending of various qualities of coal for use in the ovens, all contributed to the production of cheaper iron.

One of the attractions to the colliery companies of installing the early by-product coke ovens was their ability to use the small coal left after the run-of-mine coal had been screened. Such fine coal was always contaminated with shale, clay and stone from the floor and roof of the seams which obviously could not be hand separated as in the case of the larger coal. The impurities could, however, be separated by washing, but this added a cost which the cleaned coal could not always carry if used as an ordinary fuel.

The new coke ovens were, however, designed to use crushed coal of about a quarter of an inch down, and the economics of the process enabled it to absorb the cost of washing and crushing. Consequently, a coal washery became a feature at all the collieries where the new ovens were installed. The washed small coal was allowed to drain either in bunkers or on slow moving draining conveyors until its moisture content was reduced to 9 or 10% and then crushed.

It was considered that the local coals produced better coke if the coal was stamped into a cake before charging to the ovens, and a feature of all the local plants was a stamping machine which prepared a solid cake of coal, the full length of the oven but slightly narrower and sitting on a peel which was mechanically propelled into the coking chamber. Whilst a large measure of mechanisation had been applied to the ovens designed and built in the first 20 years of the present century, there was still much manual labour necessary. For example, the coke, after being discharged from the ovens and quenched with water, was loaded into wagons by men using large forks with tines three quarters of an inch apart to separate the fines or breeze. In a normal eight hour shift three men manhandled 100 tons of coke.

Other manual jobs consisted of winching the oven doors up and down as required for pushing and charging, hand operating the gas reversing valves, and keeping the gas collecting main free from pitch deposits by hand poking.

In the early 1920s there were many developments by the oven designers and builders which were to result in larger ovens operated at higher temperatures, with mechanical aids to eliminate the particularly heavy manual work associated with the earlier plants. The Workington battery of 1936 incorporated the most up-to-date techniques of this nature.

Remains Today

Today there are few relics left of the earlier coke making activities. Until quite recently there were traces of the ‘heaps’ where coke was made for the Little Clifton furnace. It was possible to identify the base of the heaps by the carbon impregnated earth and stones on which they had been built.

At Maryport there is still the remains of an oven, probably the oldest in the country. The (other? Ed.) beehive ovens have long been demolished. The last visible ones were buried under the spoil heaps of the Risehow colliery alongside the road on the north side of Flimby. There are (were? Ed.) considerable remains at William Pit, Whitehaven, of the old beehives. The earlier by-product ovens have all gone, but there are records of their design in the text books and catalogues of the builders.

Oxford Archaeology North

Extracts from Mill Street, Maryport, Cumbria

Archaeological Watching Brief

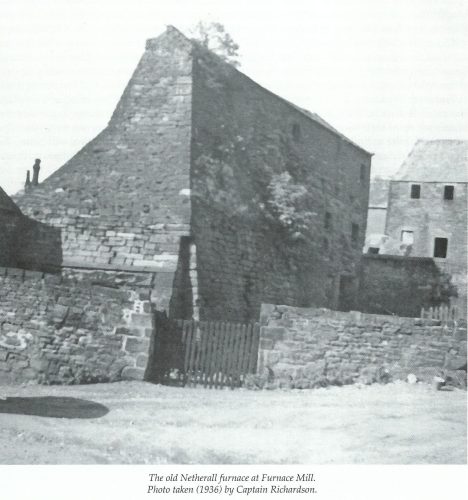

The origins of the Netherhall Blast Furnace are closely connected with the origins of Maryport itself. The Netherhall furnace was one of a group of 18th century Cumberland Blast furnaces that made early use of coke coal. The main phase of furnace construction & operation took place between 1752 & 1783. The site of the furnace was leased by Humphrey Senhouse II to 7 partners who built & managed the furnace.

Maps of 1756 & 1769 show a simple arrangement with 2 rectangular buildings set at right angles with an open watercourse, (leat), alongside. A 1770 map shows a much-expanded complex of buildings & a study in 1973 by TR Slater interpreted the site to contain the furnace, bellows & charging house, casting house, two sets of coke ovens, the leat, dwelling houses, storage areas & other buildings. The furnace leat was originally built as a branch of an earlier corn mill leat, at Netherhall to the north-east, which was split into the furnace leat & the by-pass leat, the by-pass being later adapted to provide power for the corn mill by the furnace.

Documentary evidence shows that a corn mill existed on the Netherhall estate, (but not the furnace site), prior to the construction of the blast furnace. An indenture of 1752, between Humphrey Senhouse II & the members of the Netherhall Furnace Company was for a portion of land which comprised, ‘All that Watercorn mill & appurtances known as Netherhall Mill. Also, the kiln & stable of said miln & appurtances called the Back of the Mill to Netherhall Bridge’. There was a wayleave within the indenture which permitted extensive alterations to the land between Netherhall & the furnace site, in order to supply the furnace with a water supply. This involved the construction of a branch leat from the pre-existing Netherhall mill-leat & allowed the developers to: ‘…cut trenches & conduit for water from the mill race at the north east of the kiln in such a convenient manner as the same can be best afforded across the High Road leading to Netherhall Bridge to the aforesaid Mill into the inclosure called Calf Close & so directly on the south-east side of the said inclosure & close there called Barn Croft, in the nearest & most convenient manner at the foot of Moat Hill covered with stone until brought into Calf Close…’

In 1783 the furnace was put up for sale & through lack of buyers, reverted to the owner Humphrey Senhouse II. The next reference to the furnace site within the Senhouse manuscripts dates from 1787 & is a letter from a Mr Smith to Senhouse, which refers to a lack of an adequate water supply as a factor in the potential cause for the furnace’s failure. Recent research has placed the lack of an adequate water supply as being the prime reason for the furnace’s failure. Slater states that since the furnace not only shared ‘the [water] supply with the mill, with which it was bound not to interfere, but the system itself had a very low storage capacity to tide it over in times of drought’ Improvements could not be made due to a clause which prevented the heightening of the dam, a scheme of works which would have flooded Netherhall itself.

Despite the existence of the estate corn mill in the documentary sources consulted, there is no reference to the corn mill on the furnace site prior to 1809, which was built on the line of, & using, the furnace leat. Mapps of 1869 & 1881 indicate that part of the expanded furnace complex was included with the lease for this mill. Late adaptions & expansions in the area of the furnace included the construction of a saw mill to the east of the furnace site prior to 1864 & a slaughter house also located east of the furnace, built pre-1899. By the 1950’s, the furnace was in use as a builder’s yard & during the 1960’s, a number of changes in the area included: a bus station built adjacent to the slaughter house, the demolition of the saw mill, the furnace site being used as a haulage, & subsequently County Council Highways depot. Finally, the slaughter house was converted to an ambulance station. These later developments do not appear to have affected the Furnace Corn Mill which, though derelict, survived as a standing structure until it burnt down in 1976.

A 1993 excavation of the corn mill site revealed, at its northern end, a number of structures which relate to the corn mill, including a mill race, leat & water wheel pit. The top course of the stone-lined waterwheel pit showed signs of heavy disturbance, suggesting later modification of the original waterwheel & mill-leat. The presence of industrial residues incorporated within both fills in the area of the waterwheel pit suggested that one of the walls was a feature post-dating the initial operation of the blast furnace & that this indicated post blast-furnace modifications to the water system. There were also remains of the mill race, which was constructed of mortar bonded, large, worked rectilinear sandstone blocks & had a sandstone flag-lined base. It is believed that it continued for a considerable distance underneath part of Maryport & Senhouse Park to join the River Ellen at a point above the high tide mark, so as to maintain a constant water supply. Water flows were also controlled by means of sluice gates. The combination of the mill race, leat & several other structures provided the main water power source for the corn mill.

The waterwheel pit & millrace were both filled by accumulation debris which was loose, gritty silt material, reaching a maximum depth of 3.07m. It contained a variety of modern debris, including oil drums, stones of all descriptions, bricks, slates, fragments of large mechanical objects & domestic household waste. The nature of these fill components testifies to the fact that the waterwheel & mill race were only fairly recently filled in.

Overlying the water power elements of the site was a demolition layer which contained a number of quern stone fragments, proving that this was the location of the corn mill. In addition, iron mechanical components found included several paddle-wheels & a bronze housing for a bearing, suggesting that the nearby water channel was used for motive power.

A circular structure, with a diameter of 2.92m & an overall height of 0.45m, constructed of mortar bonded, large, worked sandstone blocks, was located adjacent to the north east extent of the mill leat. A slot 2.15m long & 0.29m deep was cut into the structure. Given its location adjacent to the waterwheel pit & proximity to the corn mill, it was concluded that this circular structure was probably a corn drying kiln, especially since the sandstone flagged floor appeared to have been affected by burning. A drying kiln for drying damaged corn was mentioned in an 1879 study by Addison, which was fuelled by coke produced from the site coke ovens.

Castle Hill (Maryport) Local History Group

The Maryport (Netherhall) Furnace 1752-1783

David Malcolm

13 October 2021

[email protected]

This article is about the Maryport or Netherhall Furnace and my two main sources for the story are:

- “The Iron and Steel Industry of West Cumberland, An Historical Survey” by J Y Lancaster and D R Wattleworth. Pub. 1977

- “The Archaeology of the West Cumberland Iron Trade” by H A Fletcher F.R.A.S. Pub. 1880

“Coming to the period when the smelting of iron in blast furnaces, with coke as fuel, became an established commercial success, which was not until after 1735, we find that about the middle of the 18th century such furnaces were built within the Cumberland Coal Field, (most or all of them with foundries attached for making iron castings,) at four different places, viz., Little Clifton, Maryport, Seaton, and Frizington, but little success seems to have attended them, for these works all seem to have been abandoned after short careers, except those at Seaton. About 1750, or possibly a little earlier, Messrs. Cookson & Co., who worked coal mines at Clifton and Greysouthen, erected a blast furnace near Little Clifton, on the banks of the river Marron, which supplied the needful waterpower for blowing.”

“This furnace at Clifton was no doubt abandoned when Mr. Cookson’s colliery was ” drowned out ” in the year 1781.” Fletcher 1880

This furnace is recorded as have urgently cast additional cannon balls, to arm the canon being rushed from Whitehaven Castle to take part in the siege of Carlisle Castle by the Jacobite Army as it retreated from Derby in 1745.

“The second important blast furnace, built in West Cumberland was at Maryport or Ellenfoot as it was then called by a partnership comprising James Postlethwaite of Cartmel in Furness, William Postlethwaite of Kirkby in Furness, William Lewthwaite of Kirkby Hall in Furness, Edward Gibson, John Gale, Thomas Hartley, and Edward Tubman, all merchants of Whitehaven.” Lancaster and Wattleworth

“They obtained a lease from Humphrey Senhouse of a site adjacent to the River Ellen for the purpose of erecting furnaces and forges …” Lancaster and Wattleworth.

The three gentlemen from Furness were involved in mining ore from that area, and would have been familiar with the making of iron with charcoal – were they perhaps involved with the furnaces at Duddon or Backbarrow? Indeed, production of iron in the Furness area would ultimately be threatened by a shortage of timber to produce charcoal. Were they perhaps seeking to secure their business by moving it to a coal producing area? The Whitehaven merchants involved in the partnership would probably have been providing the finance.

Interestingly Mr Fletcher quotes from the Deeds of 1752 that the Lease and Release included of “… buildings, quarries and lands upon which to erect furnaces and forges, with power to deepen the River Ellen between the works and the harbour, for a term of fifty years at the yearly rent of £52/10/-“ This document doesn’t seem to make any reference to the construction of a mill race upon which the entire power supply to the furnace would depend – unless the initial intent was to power the furnace from the River Ellen directly?

However, in November 2002 Oxford Archaeology North surveyed the area as part of the Mill Street, Maryport – Archaeological Watching Brief and reported.

3.2.4 An indenture of 1752, between Humphrey Senhouse II and the members of the Netherhall Furnace Company, was for a portion of land which comprised ‘All that Watercorn mill and appurtances known as Netherhall Mill. Also, the kiln and stable of said mill and appurtenances called the Back of the Mill to Netherhall Bridge’ (D/Sen/1752-84). There was a way-leave within the indenture which permitted extensive alterations to the land between Netherhall and the furnace site in order to supply the furnace with a water supply. This involved the construction of a branch leat from the pre-existing Netherhall mill-leat and allowed the developers to: ‘… cut trenches and conduit for water from the mill race at the northeast of the kiln, in such a convenient manner as the same can be best afforded across the High Road leading from Netherhall Bridge to the aforesaid Mill into the inclosure called Calf Close and so directly on the south-east side of the said inclosure and close there called Bank Croft, in the nearest and most convenient manner to the foot of Moat Hill covered with stone until brought into Calf Close.. ‘

Building of the furnace was completed in 1754 and was reported by Humphrey Senhouse in his day book:

“The Furnace erected by Messrs Gale, Gibson, Hartley, the two Postlethwaites and Lewthwaite began to blow on Friday, ye 12th of August 1754 and ran the first metal of Iron on Saturday ye 13th in the afternoon. Mr Curwen of Workington, Messrs Christian, Charles Lutwiche, most of the company and myself being present. The performance was much to our general satisfaction.”

Where was the Maryport Furnace?

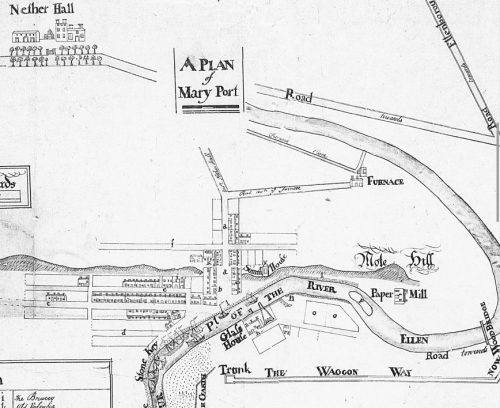

This is an extract taken from “No 1 copy, Old plan of Maryport kept at Netherhall without date but supposed to have been made between 1749 and 1756.” Which clearly shows the Furnace, the “Furnace Race” and a road marked as “Road towards (?) Furnace”

Next image is from the Town Plan from 1760. The Furnace is clearly shown, with the Furnace Race. Crosby Street is now being developed.

On the reverse of this map the actual building plots sold by Humphrey Senhouse have been sketched and numbered, together with a list of the occupants. In the image I show below, it is a little confusing as features of the map show through onto the sketch of the building plots. However, the Furnace is shown in a little more detail. The sketch even shows the furnace blowing smoke!

Although the furnace ceased operation in 1783, its physical extents survived to 1963, and so I have used this rather splendid map from about 1878 to show the location of the furnace, and its relationship to the rest of the town. NB at this date Curzon Street terminated at Station Street, the only through road being Meal Pott.

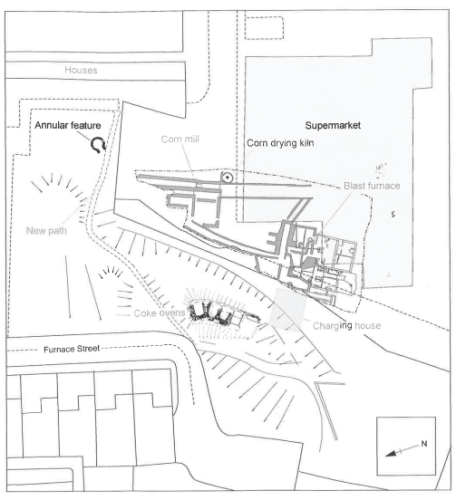

Finally in this section, I need to locate the Furnace directly into the modern context and to illustrate this I go back to the Oxford Archaeology North survey of the Mill Street, Maryport – Archaeological Watching Brief.

In this illustration from the report the archaeological remains of the furnace, the adjacent corn mill and the coke ovens on the high ground on Furnace Street are superimposed onto the modern street plan.

The Houses noted are on Mill Street and the Supermarket was built as the Coop, and now houses B&M Home Bargains.

In this undated photograph the Furnace is visible together with the Managers House. It has been taken from the river bank below where the railway bridge now stands.

Technical Descriptions and Specifications

Lancaster and Wattleworth describe the furnace in its original 1752 specification as follows:

“… The furnace they built was a large one for those days, its dimensions being 36 feet from hearth base to the charging level. The hearth diameter has been recorded as 8ft and 12ft at the intersection of the two truncated cones forming the body of the furnace.”

Fletcher adds

“… It is square in cross section and appears to have been about 36 ft high and 11 or 12 ft on diameter at the “boshes“ or widest part. It is built of red sandstone, of excellent workmanship and the “tymp arch” which contains the aperture for casting is almost perfect.”

Note the original lease from Humphrey Senhouse referred to “buildings, quarries and lands …” which might refer to access to Sea Brows Quarries, from which a fine red St Bees Sandstone would have been available.

Continuing to describe the furnace Lancaster and Wattleworth continued:

“… That it was intended to run on coke is evidenced by the installation of ovens for making that material, more or less alongside the furnace….” “At the beginning of operations, the blowing apparatus would be a pair of large leather bellows operated by a water wheel. It is possible that the blast delivered by the bellows was not powerful enough to provide the necessary heat from the coke and that charcoal was resorted to because of this.”

“Information is available that charcoal was brough across the Solway from Scotland for use in the furnace …”

By 1777 it was decided to try and improve the operations of the furnace with the installation of new and more efficient bellows. Lancaster and Wattleworth continued:

“…the leather bellows, were replaced by what were referred to as iron bellows. From the description, however these were obviously cylinders and pistons, but still operated by waterpower. From the dimensions … the volume of air theoretically produced by this equipment was 6,000 cu. ft. per minute.

The new bellows were described in the Cumberland Paquet of April 1777 as follows:

” We have heard that a pair of iron bellows are placing at Netherhall Furnace; they were cast at Birsham, near Wrexham, and weigh, exclusive of the pistons, 146 cwt. The quantity of air discharged by these is astonishing. Every sink of the piston is calculated to produce 126,000 cubic inches; one revolution of the wheel sinks the piston 8 times, and the wheel revolves 5 times in a minute; so that the whole quantity of air produced in one minute is 5,040,000 cube inches.”

After 31 years of operation the Furnace was offered for sale on 26 May 1783, and it is perhaps worthwhile unpacking the description of what is being offered for sale.

“All those commodious well-built IRON WORKS called Netherhall Furnace … The Blast is supplied by Iron Cylinders of 6 feet diameter and amply supplied with water. Also, a CORN MILL, called Netherhall Mill, the Fishery of the River Ellen and one field or Inclosure called “Yanham” adjoining said furnace containing about 10 acres.

Note Netherhall Mill is on the River Ellen, upstream from the Furnace at the place where the Furnace Mill Race is taken from the river.

“The Furnace is in an eligible situation for either being supplied with charcoal or coke, being only about 400 yards distant from the harbour of Maryport …”

“The buildings belonging to the Furnace include:

- Three large coal houses sufficient for nearly a year’s blast

- Three commodious houses for the storing of Iron Ores

Three dwelling houses for workmen - A large and convenient casting house, with a very good furnace, both adjoining to the blast furnace, by which the Foundry Branch may be carried on to the greatest extent

- 17 ovens for charring coals, built on an improved plan, which make a cinder superior to any other method

- A neat, well-built dwelling house, most agreeably situated and convenient for the Works.

The Furnace Stack Buildings, Wheels and Bellows, Casting House and Air Furnace are all in the very best condition, fit to work immediately…

Also, to be sold that piece or parcel of Ground or Yard, commonly called the Furnace Yard, situate in Nelson’s Lane in Maryport, in which there is built a very good stable.

Note: In July 1752 William Postlethwaite bought two plots of land on Nelson St from Humphrey Senhouse. One with a frontage of 28 yds and 26 yards back, and the second with a frontage of 11 yards and 22 yards back. In the Senhouse Register of Grantees these are described as being on Nelson Lane and extending to Grant No 26 on Shipping Brow.

Why is it felt necessary to advertise the fact that the yard contains a “very good stable”?

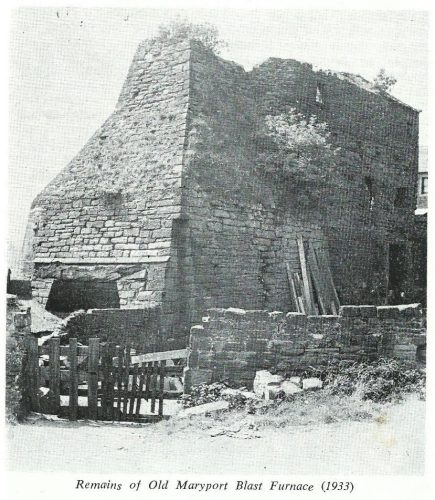

Lancaster and Wattleworth finally report that in 1933 a very thorough examination of the properties was made, which reported:

“… the outer red sandstone casing of the furnace was in sound condition. The bridge spanning the space between the furnace top and the high ground behind was intact but starting to decay. It was over this bridge that the ore, coke and flux (limestone)were wheeled for tipping into the furnace. What were assumed to be coke ovens were built into the high bank and consisted of rectangular brick-built chambers

Overall, this offering is for an integrated works taking Iron ore, processing it to cast iron and having the capability to cast specific products. It is also processing coal and turning it into coal to supply the bast furnace and seems to have stabling facilities. The operation is also providing 3 dwelling houses for its workmen.”

What did the Furnace look like?

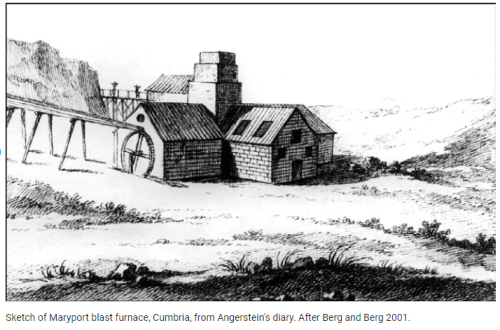

First there is the curious case of a Swedish gentleman, a prototype industrial spy, one Reinhold Rucker Angerstein. Angerstein was an assessor for the Swedish Royal Mining Council, and the Director of Heavy Forging for his nation. The Swedes were concerned about the threats to their supremacy as the main exporters of bar iron to Britain during the 18th century, both from Russia and America and from technical innovations within the British iron industry. In 1753 he embarked on his two-year journey across England travelling to cities such as London, Wolverhampton, Oxford, Sheffield, London, Liverpool, and Carlisle, making a point of visiting as many blast furnaces as he could. … and he naturally visited Maryport!

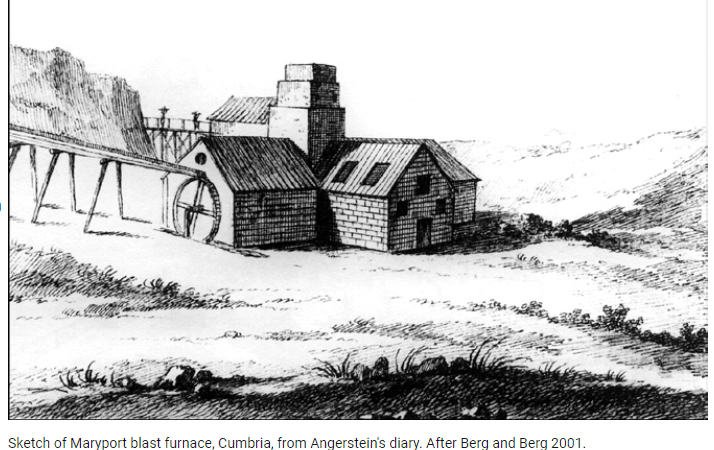

One of his journeys in 1754 took him to Maryport where he sketched the blast furnace, then to Clifton where he reported coke being used to fire the furnace. Coke was also used at the Maryport Furnace, with the coke ovens being along Furnace Road ABOVE the Furnace.

This seems to me to be a somewhat romantic image but let’s perhaps view it as a source of information, rather than a photographic image of a scene. Remember Angerstein is collecting information, not seeking to exhibit artworks. In this context it clearly shows a mill race and a water wheel being used to power the furnace and a gantry from a cliff face (where the coke ovens are) that seems to be used to load the furnace.

Context, Logistics and Economics

In 1752, a partnership is formed to build and operate a blast furnace at the new development of Maryport. Why?

The partnership comprised 3 gentlemen already concerned with the iron trade in the Furness peninsular. Here the furnaces were powered by charcoal and Fletcher suggests that it was “… not an improbable conjecture that they may have previously had to do with the making of iron with charcoal, —for which that country was once prominent, —and having been literally burnt out by the failure of the supply of timber, had to move their business into a coal producing locality …”

Is there demand for iron products in West Cumberland? West Cumberland demand in the 1750s is not clear apart from domestic hearths and ovens; horseshoes; and nails. It is a rural economy. Even so in “North Country Life, Vol II, Edward Hughes 1963” reports Humphrey Senhouse having to obtain iron plates for his salt pans at Flimby from Mr Muncaster of Newcastle, and he had even been forced to use some old iron to make new fire grates at Netherhall. Walter Lutwidge, a well-known Whitehaven merchant, also complained of having to obtain rod iron for making nails and hoes from Bristol, and from Cookson’s at Newcastle. Lutwidge also complained that the Clifton Forge (at Bridgefoot) sells no iron, making only enough for its own consumption and that the forge “… at a place called Backbarrow is so remote that there is no getting it brought hither (to Whitehaven) under 7/6d per tunn at the least.”

It would seem then that the Furnace venture was aimed at meeting demand for iron from West Cumberland. Such a venture was going to need a good local supply of coal, and access to a harbour into which ironstone could be imported. Ellenfoot (Maryport) seemed to meet these requirements. There was abundant coal available close by and it was a good natural harbour that was already being used to export coal in limited quantities to Dublin and agricultural products to the new industrial towns of Lancashire. Furthermore, it was owned by an enthusiastic gentleman in Humphrey Senhouse.

There are two snags in this scenario – where is the ironstone to come from; and where is there a market to be found? The ironstone is clearly to be imported from the mines in Furness, given the Postlethwaite interests. Lancaster and Wattleworth note that at the time of the sale of the Furnace in 1783 an inventory was taken which identified small stocks of iron ore, limestone and coke. “The ore was all from the Furness mines – Crossgates, Inmangill and Whitriggs.” In 1795 Whitriggs (3 miles west of Ulverston) is described by James West in his “Guide to the lakes” as “… the greatest iron mines in England, where the richest ore is found in immense quantities.”

But where is the market for cast iron products in West Cumberland? Or is it the intention to export cast iron products and pig iron? In this area a larger market hopefully will come from the early industrial developments in Whitehaven and Workington together with the growth of the shipping trades locally, and the growing populations encouraged by these developments. Furthermore, given that local coal owners and merchants are already trading overseas to Ireland, Scotland and ports further afield they are probably confident of finding a market. Additionally, Humphrey Senhouse also has ambitions that seem to coincide with those of the Furnace partnership.

In 1749 Humphrey Senhouse started the development of a new town at the mouth of the River Ellen, then called Ellenfoot. There is demand from the collieries at Dearham, Ewanrigg, Flimby and on Broughton Moor to access the export market for coal that is Dublin. Shipping capacity at Whitehaven is now limited and the coal ships may have to wait up to a week for a berth at the Staiths in Whitehaven. The Senhouse plan is broadly to develop a safe harbour to meet this demand for export capacity, and then to provide facilities to support the trade – shipbuilding and repair, warehousing, seafarer’s accommodation, Inns, etc. He is probably also aware that the success of such an operation also depends upon the development of a market for imports, in the way that Whitehaven has developed the tobacco trade and Liverpool the import of cotton and other cargos from North America and the Caribbean. To this end he encourages industry to the town, together with workers, merchants and traders by making available standard building plots in a planned new town. In doing this he is clearly following the model developed by the Lowthers at Whitehaven.

In January 1749 the first land parcels are sold by Senhouse to Messrs. Sharp and Brougham, quickly followed by another in March to William Currey. The harbour improvements began without delay. At the start of the works in 1749 it is reported that “Broughton Colliery handicapped by inefficient management and high leading costs could yield but small profits. In 1749 when worked by Ewan Christian it earned a profit of only £41 1/5d on an output of 7680 tons. (Leading costs refers to the cost of transporting the coal from the pit to the dock). Of the 7680 tons of coal sold 369 were sold to the salt pans, 3713 tons to the domestic market and 3560 tons to export.

Three further land parcels are sold in 1750 and another five in 1751 including the first workmen’s housing on King St. In 1752 the first industrial development begins with the development of the Netherhall Furnace and additionally a Glass Works on the harbour side. Interestingly the Glass Works will build 60 yards of stone quay for its express use and at the same time the Furnace, as we have seen, is given permission to deepen the river from the harbour to the furnace. Does this suggest that it is the intention to import ironstone along the river to the Furnace and similarly to export finished iron goods by the same route?

In April 1754 Humphrey Senhouse entered in his daybook: “The Furnace erected by Messrs. Gale, Gibson, Hartley, the two Postlethwaite’s and Lewthwaite began to blow on Friday 12th April 1754 and ran the first metal or Iron on Saturday 13th I the afternoon. Mr Curwen of Workington, Messrs. Christian, Charles Lutwiche and most of the company and myself being present. The performance was much to our general satisfaction.”

By this date there are 51 land parcels sold in the new town of Maryport.

Meanwhile in 1761 Ironstone starts to be worked on the Curwen Estate at Harrington and supplied to the Ironworks of Spedding and Hicks at Seaton (which open in 1763) and by the end of the century to Ironworks in Aberdovey, Argyll, Duddon Forge in Furness, Halton (Lancaster), Newlands, and Leighton. It is quite possible that Maryport ships could be involved in this trade, but it doesn’t seem that the Netherhall furnace is using this local supply of ore.

Interestingly in the 1760s Maryport ships are recorded trading with ports on the River Carron where what would become one of the largest and most important ironworks in Europe was beginning to grow.

Logistics

In this section what I am interested to explore is how ironstone is transported to Maryport, and from where? How is it taken from the harbour to the furnace? Who is involved in the trade?

Lancaster and Wattleworth note “…the location of the 18th century furnaces at Little Clifton, Maryport and Seaton was determined by the availability of running water for the operation of the blowing apparatus. The proximity of ore and fuel supplies would of necessity have to be taken into consideration, but the power source would be the determining factor. In the case of Little Clifton and Seaton, supplies of ore were brought from the Frizington area by road using carts and pack horses. For the Netherhall Furnace the ore was brought by ship from the Furness area.” This remark is interesting as it confirms an even greater demand for pack horses in the area of West Cumberland between the Derwent and the Ellen and it rather ignores how the ore is taken from the ships at Maryport harbour and transferred to the Furnace charging gantry.

Peter Skidmore in his thesis “The Maritime Economy of NW England in the eighteenth century, 2009” Notes “… In the period 1750 to 1801 coal and iron shipments are the main activity of the ports with the trade in coal to Dublin being the principal element.”

A complication regarding the import of ironstone into Maryport is that the Ship Masters traded on their own account, they bought coal from the colliery, using credit provided by the coal owners, and sold it at Dublin hopefully for a profit. How is the iron ore trade from Furness to Maryport handled? Does it follow this model?

Question. What links are generated by Maryport shipping with ironworks and the coal and iron trade around UK coastal waters?

Transport of supplies and coal. Route from harbour to Furnace Street.

People

In addition to the 7 partners in the Maryport Town Census of 1765 the following head of households seem to be involved in the Iron industry:

| Richard Miers | Iron Founder 8 |

| George Bulman | Iron Founder 5 |

| Richard Scrugham | Iron Founder 4 |

| William Atkinson | Iron Founder 3 |

| Isaac Atkinson | Iron Founder 3 |

At this date the only other industries in the town are the Glassworks, the Paper Mill and the Ropery.

In addition, there are 28 labourers – and no other industry really mentioned.